Hancitor infection with Pony, Evil Pony, Ursnif, and Cobalt Strike

Introduction

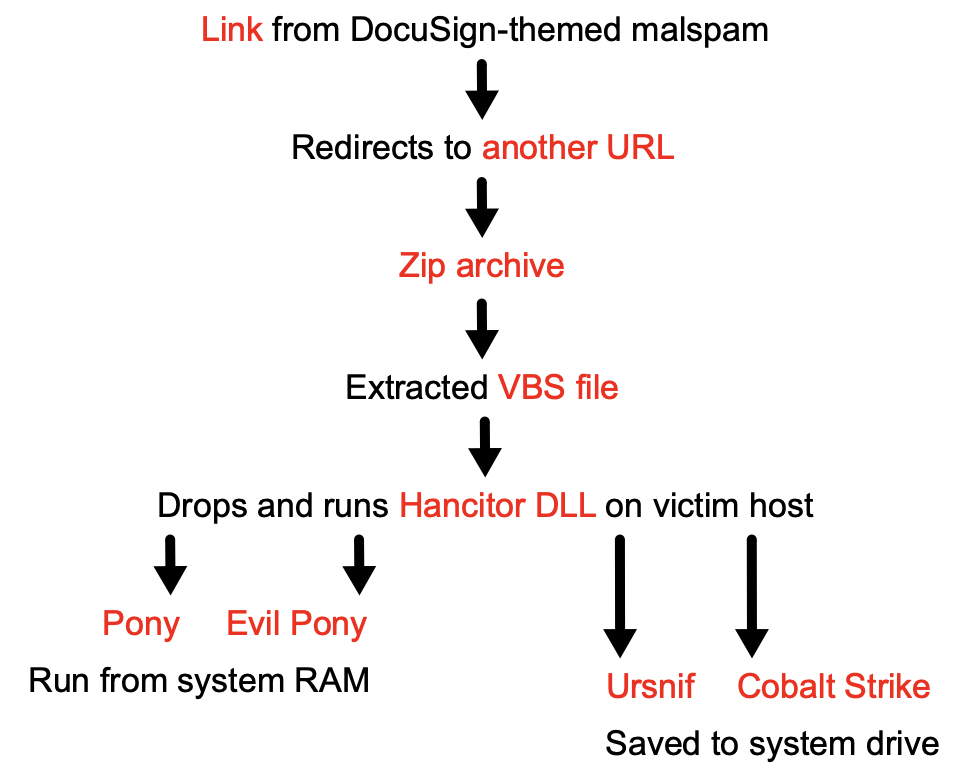

Hancitor (also known as Chanitor or Tordal) is malware spread through malicious spam (malspam). Hancitor infections most often include Pony and Evil Pony as follow-up malware. Hancitor also pushed Zeus Panda Banker as additional follow-up malware until November 2018, when it switched from Zeus Panda Banker to Ursnif. Follow-up malware usually remained Pony, Evil Pony, and/or Ursnif until July 2019, when we started seeing Cobalt Strike as additional follow-up malware.

Current malspam campaigns pushing Hancitor have been using the same DocuSign-themed email template since early October 2019. However, traffic patterns have evolved since then, so today's diary reviews indicators of a recent Hancitor infection on 2019-11-19.

Shown above: Flow chart for recent Hancitor infections since early October 2019.

The malspam

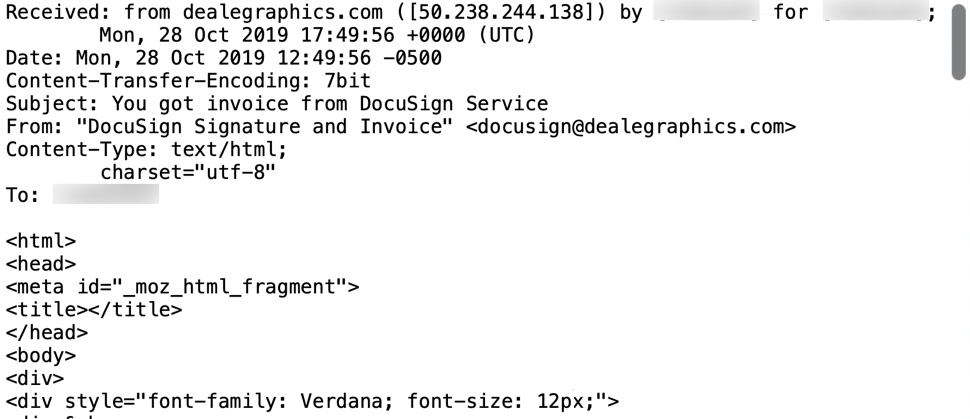

According to this Twitter thread started by @wwp96, malspam pushing Hancitor on Tuesday 2019-11-19 used docusign@galliumtech.net as the spoofed sending address, and subject lines all had the word DocuSign in them. I was not able to obtain a copy of the 2019-11-19 malspam, but below is an image of email headers from similar Hancitor malspam on Monday 2019-11-28.

Shown above: An example of headers from malspam pushing Hancitor on Monday 2019-10-28.

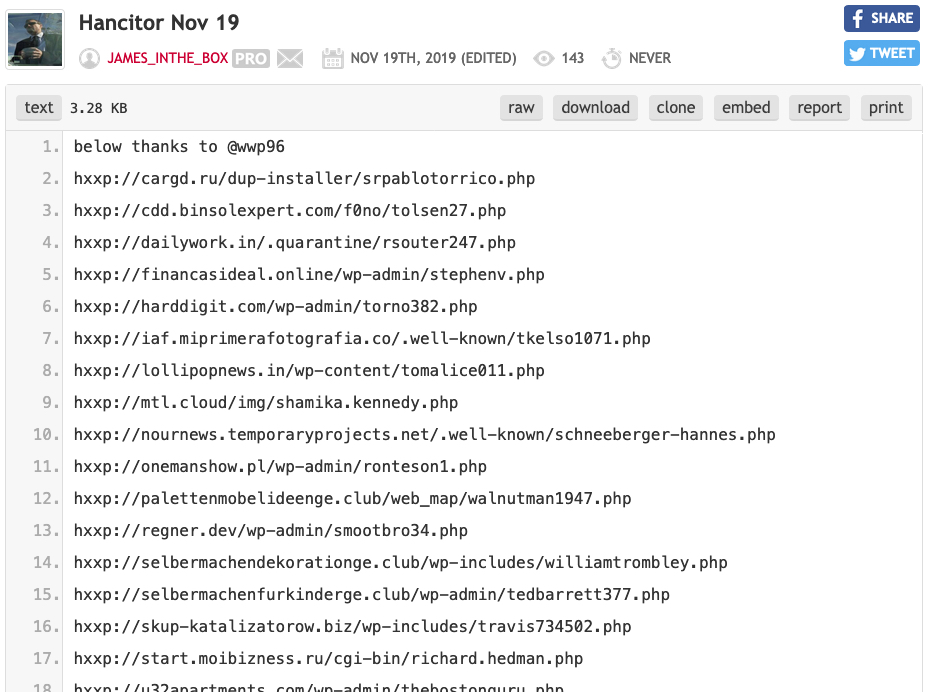

Some links seen in emails from this wave of Hancitor malspam are shown in the image below from a Pastebin post created by @James_inthe_box.

Shown above: Some links from malspam pushing Hancitor on Tuesday 2019-11-19.

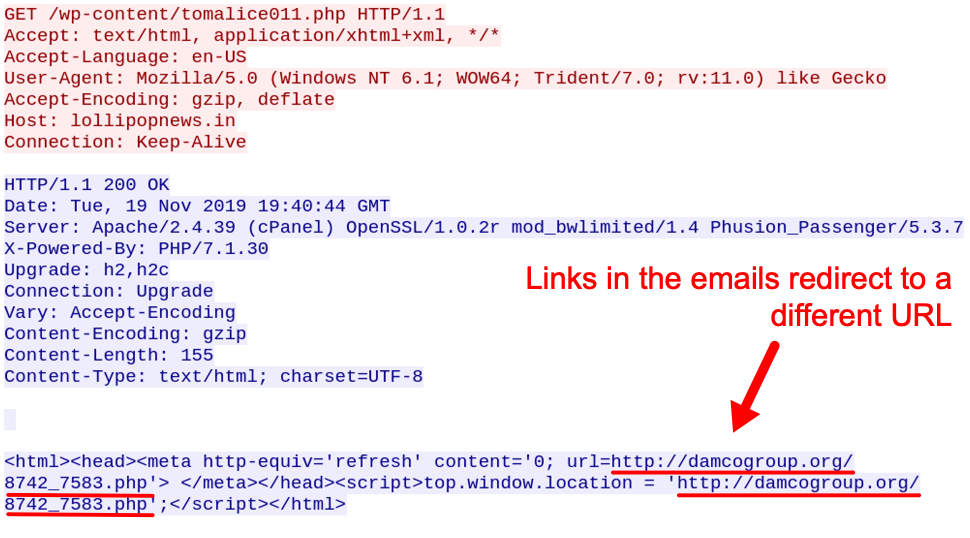

Shown above: Link from an email redirecting to another URL.

Infection traffic

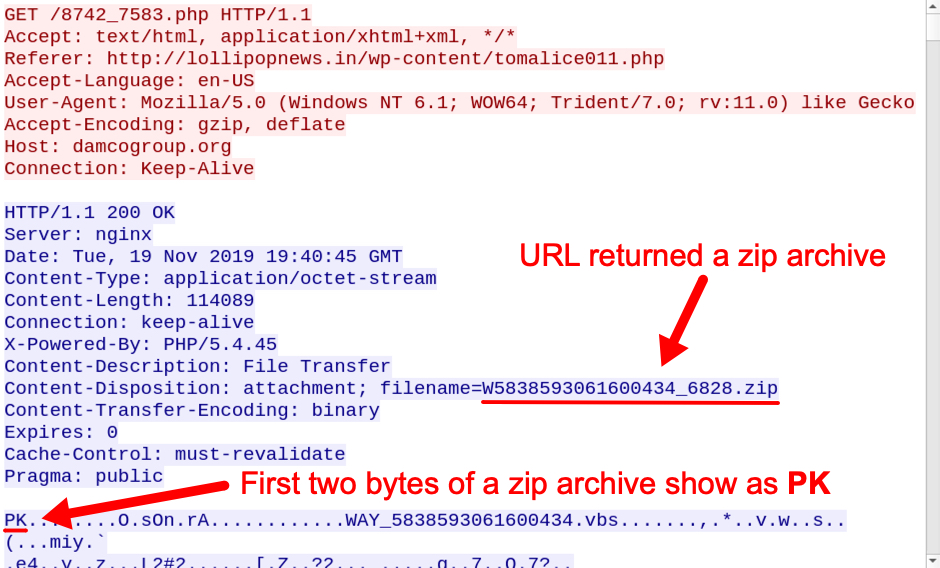

The link redirected to in the above image returned a zip archive as shown below.

Shown above: Zip archive delivered from redirect after clicking link in Hancitor malspam.

After I extracted the VBS file from the downloaded zip archive, I used it to infect a vulnerable Windows host in my lab environment.

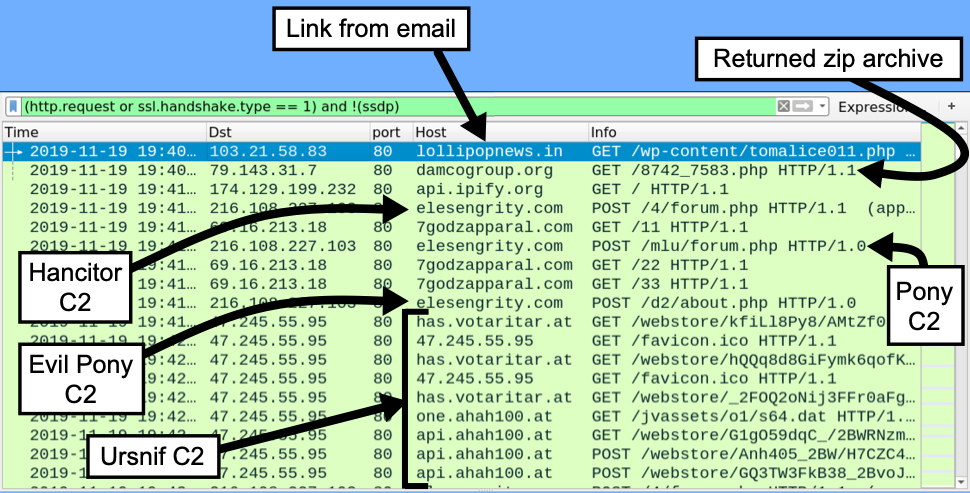

Shown above: Traffic from an infection in my lab environment filtered in Wireshark.

The initial infection in my lab environment did not have Cobalt Strike; however, when I ran the Hancitor DLL in an Any.Run sandbox, it generated post-infection traffic associated with Cobalt Strike.

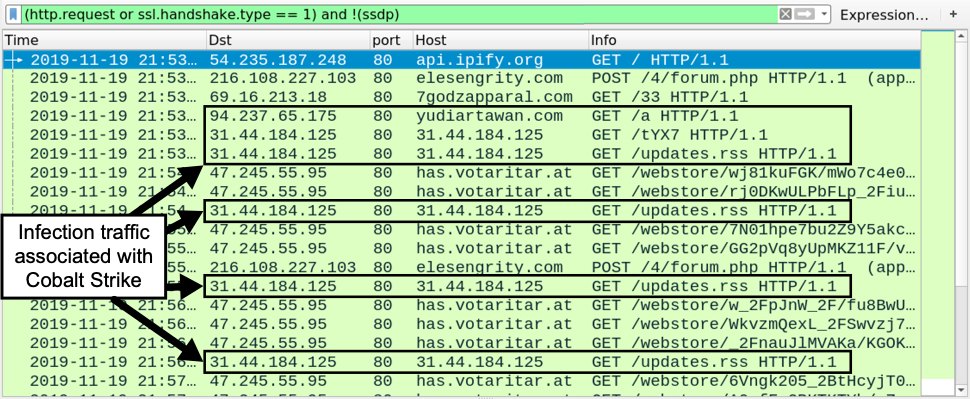

Shown above: Hancitor infection traffic with Ursnif and Cobalt Strike as the follow-up malware.

Post-infection forensics

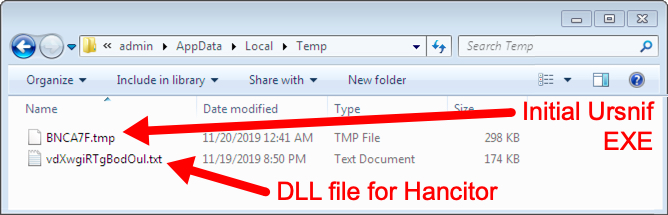

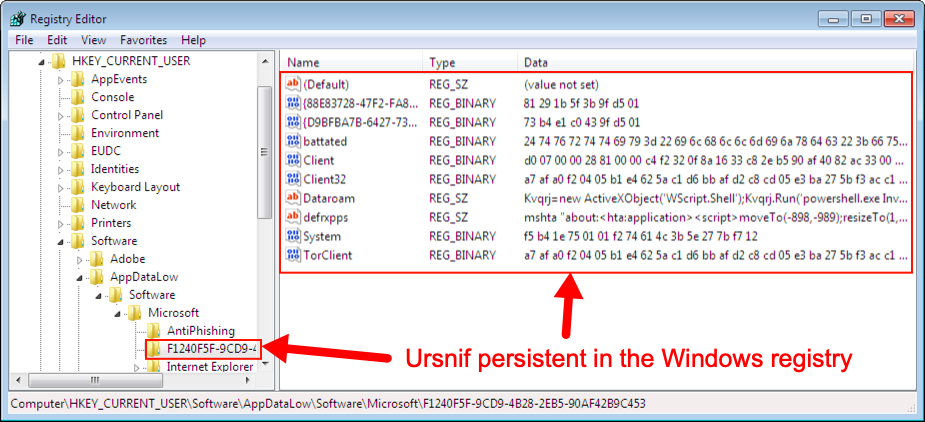

The Hancitor DLL was stored with a .txt file extension in my infected user's AppData\Local\Temp directory. I also saw indictors of the initial Ursnif EXE in the AppData\Local\Temp directory. In my lab, Ursnif updated the Windows registry to stay persistent. I did not find any indicators of Hancitor remaining persistent. After a reboot, my Hancitor infection stopped (even though Ursnif continued).

Shown above: Artifacts from a Hancitor infection with Ursnif in my lab environment.

Shown above: Ursnif persistent on an infected Windows host.

Final words

Hancitor malspam is most often caught by an organization's spam filters, so I don't consider this a high-risk threat. As always, if your organization follows best security practices, you're not likely to get infected. Up-to-date versions of Windows 10 with the latest security measures should be enough to stop this threat. If you're still running Windows 7, well-known techniques like Software Restriction Policies (SRP) or AppLocker can prevent this and other malspam-based activity.

So why do we continue to see malspam pushing Hancitor and other relatively easy-to-detect malware? As long as it's profitable for the criminals behind it, we'll continue to see this type of malspam.

Pcaps and malware from the infection covered in today's diary is available here.

--

Brad Duncan

brad [at] malware-traffic-analysis.net

Comments