Ongoing Facebook phishing campaign without a sender and (almost) without links

At the Internet Storm Center, we often receive examples of current malspam and phishing e-mails from our readers. Most of them are fairly uninteresting, but some turn out to be notable for one reason or another. This was the case with several messages that Charlie, one of our readers, has submitted to us since the beginning of 2023.

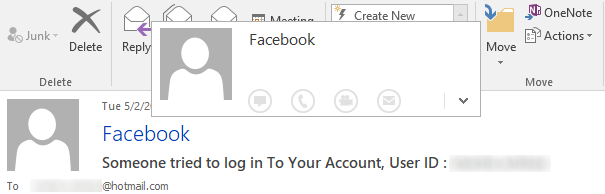

At first glance, the messages appear to be fairly straightforward Facebook phishing e-mails. The HTML body of each message appears to always be the same – it states that a user just logged into the recipient’s Facebook account from a new device and requests that the recipient verifies whether the login was legitimate.

The overall layout of the message seems to mirror legitimate e-mails from Facebook (actually, it seems clear that the author of the phishing message began its development by copying a legitimate message and modifying it, but we’ll get to that later).

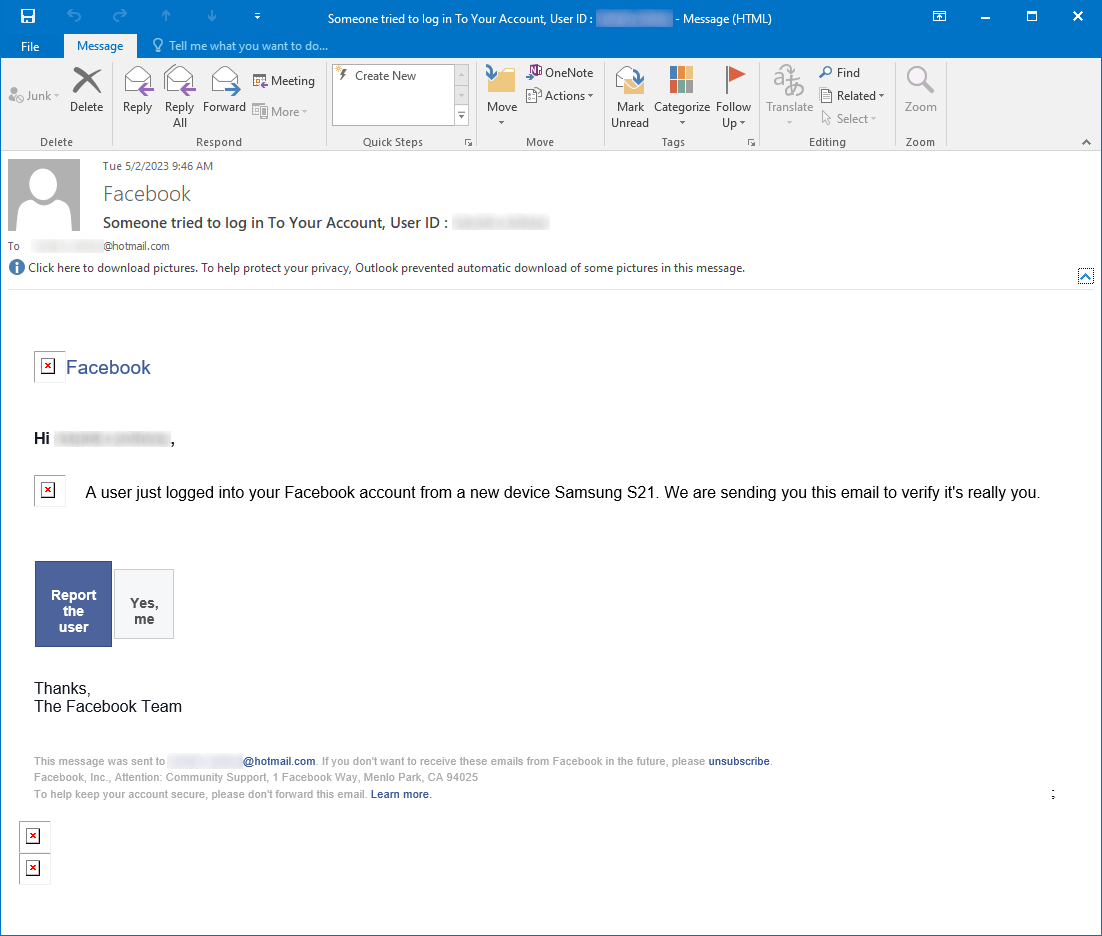

The first aspect of the messages that turned out to be unusual was the From field in their e-mail headers, which didn’t contain a valid e-mail address but only a string "Facebook" <>.

Although this string does not adhere to the requirements on e-mail header From fields set forth in the RFC 5322[1] (nor the older RFC 2822[2]), the corresponding e-mail was successfully delivered to Charlie’s Hotmail mailbox.

It would therefore seem that at least some e-mail servers out there will accept messages with From header field set in an “RFC-non-compliant” fashion… However, it should be noted that – as you may see in the image above – the Reply-To filed was set correctly in the e-mail header, which may be the reason why Hotmail decided to deliver the message(s).

In any case, the missing e-mail address in the From field resulted in the message being displayed in such a way that the recipient couldn’t easily check the address of the sender, which has certainly made the message appear more trustworthy than if an obviously incorrect sender address was displayed.

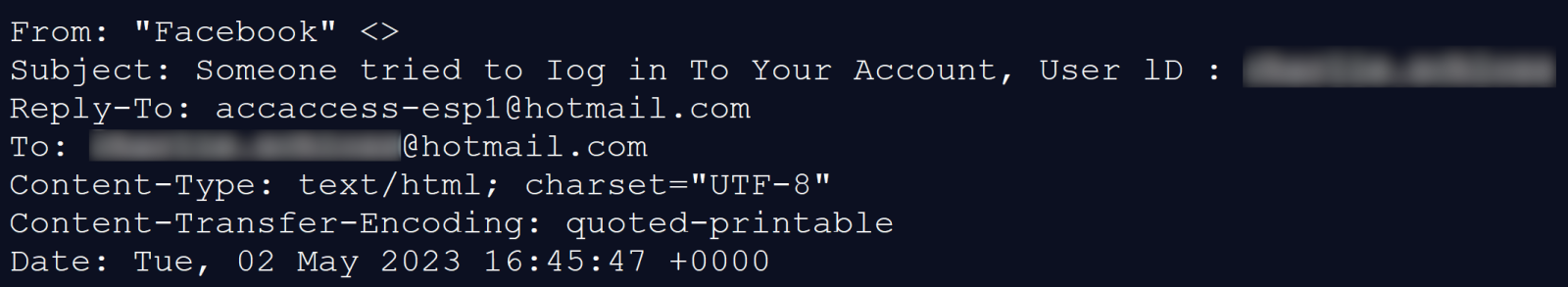

Another interesting aspect of the messages was that, except for the link from the Facebook logo and the “Learn more” link, all other href targets were set to the following string.

mailto:<[email_address]>?subject=[string]

This meant that if a recipient were to click on the links, a new e-mail message would be opened in the e-mail client the recipient would be using with the To field set to the e-mail address determined by the author of the phishing message and the Subject field set to either the string:

send+statement [recipient e-mail]

or

yes+me [recipient e-mail]

depending on which “button” the recipient would press.

It should be mentioned that the “unsubscribe” link also pointed to a “mailto” target, however, unlike the “buttons”, it wouldn’t correctly set the Subject field for the new e-mail, since the relevant string was malformed in the following way:

mailto:<[email_address]>?=bject=unsubscribe+me!

Phishing e-mails which request that a victim responds by sending a message back to their senders (or even those that open a new message window using the “mailto:” href target) have been with us for a long time, so the aforementioned approach isn’t new. Nevertheless, in this case, use of the technique is noteworthy, since the layout of the e-mail would lead one to expect that the “buttons” would cause a web page to be displayed in a browser, rather opening a new e-mail message. This behavior, on its own, might have been enough to confuse some of the less technical recipients and might have led to an increased “success rate” of the phishing. It is also a good example of why it is advisable to discuss the dangers of “mailto:” links in e-mails and on websites in security awareness courses

The last reason why this message (or, rather, this set of messages) was interesting was that the HTML body seemed to be identical in all examples we’ve seen (7 different messages sent between January and May of this year), including the malformed string in the target of the “unsubscribe” link. The only visible difference between the messages was the use of different e-mail addresses in the “mailto” links.

As we have already mentioned, it is almost certain that the message was the result of a modification of a legitimate e-mail from Facebook. Besides the fact that the text and structure of the footer of the e-mail is identical to the one that was historically used by Facebook, another aspect of the message which would appear to confirm the assumption were the two links pointing to external URLs.

The “Learn more” link pointed to the same URL as it does in legitimate Facebook e-mails, i.e.:

https://www.facebook.com/email_forward_notice/?mid=[unique identifier]

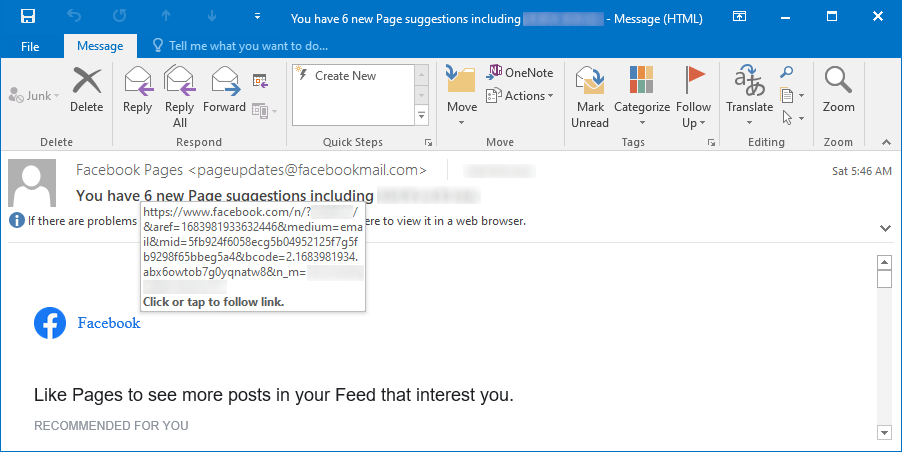

However, what was more interesting was the link from the Facebook logo in the header of the message – it pointed to the following URL:

https://www.facebook.com/n/?[name_of_facebook_page]%2F&aref=[unique_identifier]&medium=email&mid=[unique_identifier]&n_m=[recipient_email_address]

A link with URL with this format is added to the Facebook logo in legitimate messages with “page suggestions” (and possibly others), which Facebook sends out to its users.

Since it is unlikely that an author of a phishing message template would choose to use this format (always with the same page name and "unique" identifiers) for any reason apart from copying it from an original Facebook e-mail, it would seem that the aforementioned assumption is, indeed, true.

In any case, as with almost the entire body of the message, the target URL in the link from the Facebook logo was the same in all the e-mails we have seen.

One last point which deserves mention is that while there was no visible difference between the messages in question, each of them included a unique tracking pixel at the end.

While it may seem strange that the same phishing message with the same, static URL in one of the hrefs and an RFC-non-compliant sender “address” could be used for a significant timespan without any modification, since one would hope that most e-mail services would be able to detect it as malicious and block it fairly quickly, the fact that the first message we received was from January 10th and the (so far) last one was received on May 8th goes to show that phishing messages might sometimes have a much longer lifespan than one would expect…

[1] https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc5322

[2] https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc2822

-----------

Jan Kopriva

@jk0pr

Nettles Consulting

Comments