Attacking NoSQL applications

In last couple of years, the MEAN stack (MongoDB, Express.js, Angular.js and Node.js) became the stack of choice for many web application developers. The main reason for this popularity is the fact that the stack supports both client and server side programs written in JavaScript, allowing easy development.

The core database used by the MEAN stack, MongoDB, is a NoSQL database program that uses JSON-like documents with dynamic schemas allowing huge flexibility.

Although NoSQL databases are not vulnerable to standard SQL injection attacks, they can be exploited with various injection vulnerabilities depending on creation of queries which can even include user-defined JavaScript functions.

This diary is actually based on a real penetration test I did on a MEAN based application that initially looked completely safe. So let’s see what this is all about.

MongoDB collections

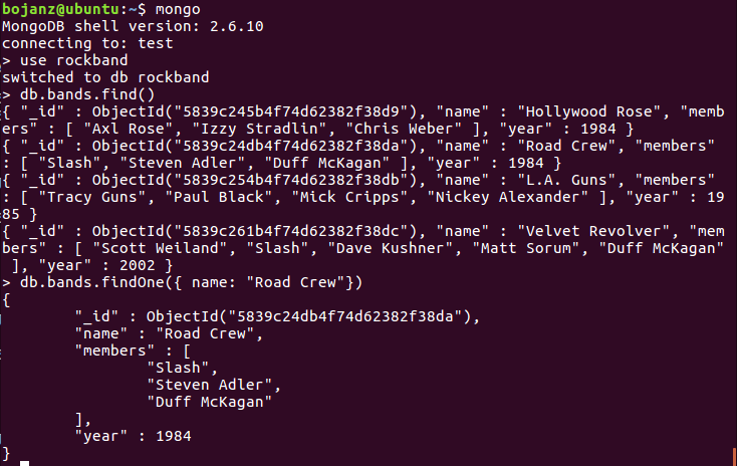

MongoDB collections are actually very similar to tables in standard databases. They will hold all sorts of different data and will allow easy (and fast!) retrieval. Here is one example of a MongoDB collection called rockband.

This collection can be very easily queried and MongoDB allows different (and powerful!) operators. For example, if in a different collection we want to query all products that have quantity greater than 25, the following MongoDB query will work:

db.products.find( { qty: { $gt: 25 } } )

This is important for us as penetration testers since we can potentially influence how a query will be executed – and we all know that as long as we can modify input parameters we can make the database do whatever we want it to do (or close enough).

Notice here that JSON, which is used to format queries, has different “dangerous” characters than those we know from SQL databases: here we care about characters / { } :

Easy development with MEAN

One of the best things of the MEAN stack is that it is very easy and simple to develop web applications. After setting some basic configuration, it is trivial to create a route to our own JavaScript function that will handle certain requests. Let’s see an example:

app.listen(port);

app.get('/documents/:id', function (req, res) {

...

This will route all requests such as /documents/a9577050-31cf-11e6-957b-43a5e81bf71e to our function. Our function can then take the id argument (a9577050-31cf-11e6-957b-43a5e81bf71e) and search for it in MongoDB.

Notice here that, although the URL looks static, it is not static at all – the GUID here is a parameter that is later used in a function. A question for you: what will your web scanner of choice try to do with this query? Will it insert a ‘ character? Does it really support NoSQL?

Easy != secure

One thing we have to be always careful about is how we handle user input. In the example above, the typical MongoDB query in the background will look like this:

var param = req.params.id;

db.collection('documents').findOne( { friendly: param } ), function (err, result) {

...

So, the id parameter is assigned to the param variable and used as the friendly parameter in the search operator. Now, one thing to stress out here is that this code is safe: no matter what we input as the id parameter, it will be treated as string, so we cannot escape from this.

However, in penetration tests I did, I encountered multiple cases when developers did something like this, presumably to make later use easier:

var param = req.bodu.id;

var searchparam = JSON.parse("{ \"friendly:\" " + param + " }");

db.collection('documents').findOne(searchparam), function (err, result) {

...

The problem here is that the developer decided to convert the param variable (which is populated directly with the id parameter taken from the HTTP body) into a JSON string.

Now, as you can probably presume, this is treated differently by MongoDB.

Exploitation time

In case above we can actually manipulate the query quite a bit. Let’s see some examples:

$ curl http://vulnsite/documents/ -d "id={ \"\$ne\": null }"

What did we do here? We supplied the id parameter in the body of a HTTP request. Since the code will take its value and compose a JSON object, this will be our final query:

{ friendly: { $ne: null } }

Interesting! So we will actually retrieve the first document from the collection!

What about other documents? It looked as the id parameter is a long GUID which cannot be brute forced. But, we can use some powerful operators that are supported by MongoDB, such as this one:

{ "$regex": "^a" }

So the search operator will be:

{ friendly: { $regex: "^a" } }

And this will retrieve the first document whose GUID starts with the character a. Nice! We can now retrieve things character by character and do not have to brute force it any more. And just in case we have some kind of WAF (does your WAF “understand” NoSQL), we can even modify it a bit:

{ friendly: { $in: [ /^a/ ] } }

This will result in the same document.

As we can see, NoSQL databases and applications that use them can also be quite vulnerable to injection attacks, so we should never underestimate what an attacker can do that can manipulate input parameters: we should always properly filter and sanitize them.

MongoDB actually supports quite a bit of search operators that can be used in this example – you can read more about them at https://docs.mongodb.com/manual/reference/operator/

As NoSQL databases are becoming more popular, I am sure that we will see new and innovative attacks against them. Interesting time is coming for sure!

| Web App Penetration Testing and Ethical Hacking | London | Mar 2nd - Mar 7th 2026 |

Comments

Easy != secure

or

Easy == (! secure)

?

Anonymous

Dec 8th 2016

8 years ago