The new "LinkedInSecureMessage" ?

[This is a guest diary by JB Bowers - @cherokeejb_]

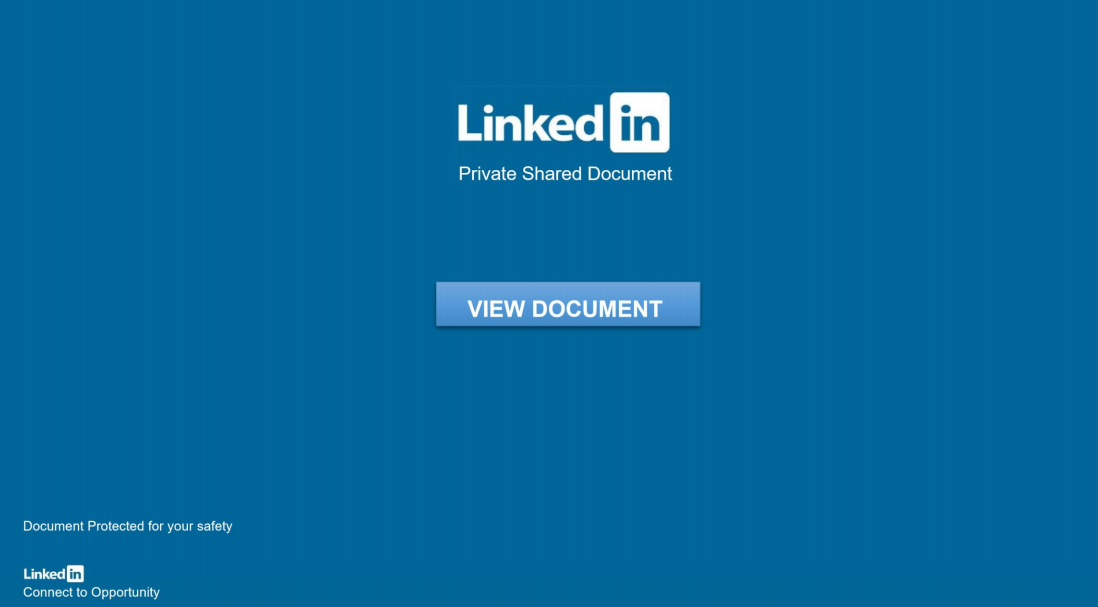

With all the talk of secure messenger applications lately, I bet you’d like to have just one more, right? In the past few weeks, we’ve noticed a new variant on a typical cred-stealer, in this case offering itself up as a new, secure messaging format used over the career website LinkedIn.

There’s only one problem with this… there is no such thing as a “LinkedIn Private Shared Document”.

Not Quite Secure

Victims will receive an ordinary message, likely from someone which they already are connected with. These are not from the more recent, unsolicited “InMail” feature, but a regular, internal “Message” on LinkedIn. There is nothing interesting about the message, although it contains a 3rd-party link, claiming to be a “LinkedInSecureMessage” which serves up the nice-looking pdf file shown above.

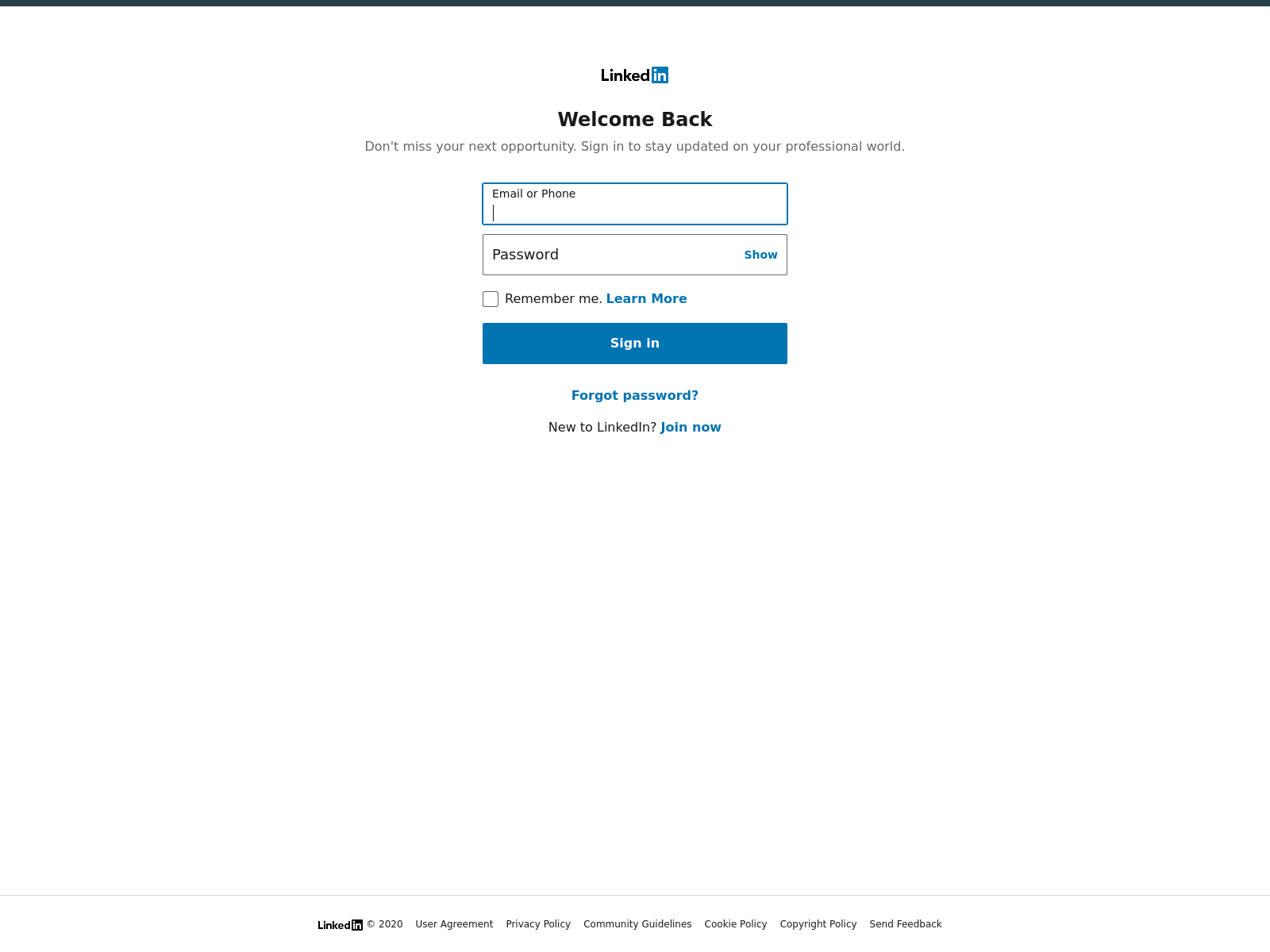

If you click “VIEW DOCUMENT,” it opens up a convincing LinkedIn login page. The example below was originally hosted at dev-jeniferng153(.)pantheonsite(.)io [1]:

This page comes complete with links directing you back to the real LinkedIn.com site, and as well as a cookie called “test,” which is backdated to 1969.

A bit deeper

I wanted to look at a selection of these domains, so I used Urlquery to find similar domains, and as well, used VirusTotal to search for similar 2nd-stage documents. A common theme here is the use of websites that may also have legitimate work purposes, for example, appspot, firebase, and pantenonsite. The sites use major ASNs including Fastly, Google, and Microsoft, making basic network traffic analysis for the end-user also not so useful.

Here are a few example domains:

dev-jeniferng153.pantheonsite(.)io fluted-house-283121.uc.r.appspot(.)com dev-cloudvpds100.pantheonsite(.)io earnest-sandbox-295108.ey.r.appspot.com

As you can see after reviewing dozens of these domains, blocking the domains, or even some type of regular expression based on known URLs is not going to get very far. If you’re not able to block these sites or their corresponding IP addresses altogether, to prevent attacks like this you’ll need to focus on the human element, and of course enforcing good security practices, like avoiding password reuse across websites.

I found several similar samples on Virus Total, for example sha1 f5884fd520f302654ab0a165a74b9645a31f4379 - Japanbankdocument (1).pdf.[2] All the files I examined used a variety of other generic or known company names, followed by the word “document,” and they had similar metadata in the pdf files. This file is currently flagged as malicious by only 1/62 vendors reporting to VirusTotal (Microsoft alone flags it as a malicious, phishing document).

A 2nd document sampled, currently scores a 0 on VT, with just the very last part of the file name, “document.pdf.”. I used Didier’s Pdf Analysis tools pdfid and pdf-parser [3] to look at samples of the documents; below are the highlights:

PDFiD 0.2.7

PDF Header: %PDF-1.7

obj 50

endobj 50

stream 6

endstream 6...

xref 1

trailer 1

startxref 1

/Page 1...

/XFA 0

/URI 2 ← Here we can see there is a URI present.

/Colors > 2^24 0

>>

obj 50 0 ← Using pdf-parser we find the next-stage phishing link in pdf object 50

Type:

Referencing:

<<

/Flags 0

/S /URI

/URI (hxxps://dev-jeniferng153.pantheonsite(.)io/document(.)zip)

>>

The real danger here is when the campaign targets high-value targets, using their accounts to target more and more of their LinkedIn contacts, or pivot into stealing credentials which would create more access for the adversary, for example, a Microsoft 0365 credential-stealer, like what was shown in a similar, 0365 Phish [4].

Again the main advantage here for the attackers is by compromising accounts, they are provided with a way to reach out convincingly to colleagues, friends, and family of the victims. This provides yet another way an adversary can make the most out of a hacked web server, by hosting countless domains like these, for phishing.

The Human Element

If you see any more LinkedIn messages like this, of course, you’ll want to let that person know out of band that their account has been compromised and that they should update their LinkedIn password, as well as report the abuse to LinkedIn. They’ll need to let all their LinkedIn contacts know their account has been used by someone else. If they have unfortunately used their LinkedIn password on any other sites, those passwords should also be changed as well.

While not very complicated in terms of the malware or tactics used, this is certainly the type of campaign you’ll want to watch out for, and train your colleagues to watch out for, specifically. Since the message is also based on LinkedIn, you may of course want to block, or forbid with policy, the use of social media at work altogether. This choice may not be a good culture fit with many organizations these days, although campaigns like this provide a good reason to consider encouraging employees not to use social media or other personal websites on their work computers.

There are some other general tips for avoiding similar phishing emails on LinkedIn’s page for Identifying Phishing, and also on their page for Recognizing and Reporting Scams [5,6].

JB Bowers

@cherokeejb_

References:

[1] https://urlscan.io/result/fc3ce0f8-f327-44d0-841a-a216d5f782db/

[2] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/4f09b9b73008dd1e7c074f5c1b9687ce41aea29006300f4617c1a894bd8864e6/detection

[3] https://blog.didierstevens.com/programs/pdf-tools/

[4] https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/case-phishy-inmail-vasyl-gello/

[5] https://safety.linkedin.com/identifying-abuse#Browsing

[6] https://www.linkedin.com/help/linkedin/answer/56325

| Reverse-Engineering Malware: Advanced Code Analysis | Online | Greenwich Mean Time | Oct 27th - Oct 31st 2025 |

Comments