Why Does Emperor Xi Dislike Winnie the Pooh and Scrambled Eggs?

China made big news last week by amending its constitution to allow President Xi to stay in power beyond the normal 10 years. While the move found great support from the Chinese party elite appointed by Xi, others in China are not all that happy about Xi being given powers not attained by anybody in China since Mao. The Chinese censors have long had a pretty tight grasp on social media in the country in order to curb any dissent. For example, Chinese censors in cooperation with service providers in China have used automated tools that eliminate certain key terms from social media discussions. But we all know that signature-based filtering of “known bad words” is tricky.

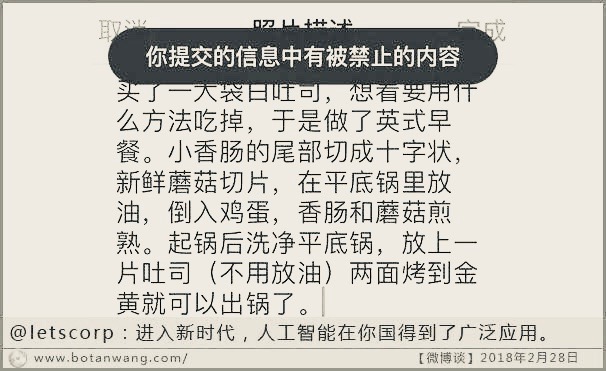

Initially, Chinese users of services like WeChat used “code words” to express dissenting ideas. For example, Xi is often compared with Winnie the Pooh and images of Winnie the Pooh are used instead of images of Xi due to their apparent resemblance to each other. Of course, Chinese censors caught on to this, and now block images of Winnie the Pooh. Another evasion technique is derived from Chinese comedy. Chinese jokes often use wordplay by replacing words with others that “sound alike” (homophones) taking advantage of different tones used in Chinese. This technique has then been used in internet chat rooms by replacing restricted vocabulary. But in particular, on WeChat, this has led to some interesting blocks. For example, recently this recipe for scrambled eggs was blocked and widely circulated as an example of an interesting false positive:

The black banner indicates that the message was blocked, or as Google translates it “Banned and Eaten” which is sort of appropriate given the context of the message. The specific keywords filtered are “the end  of a small sausage”.

of a small sausage”.  turns out to be a homophone of

turns out to be a homophone of  , which means “Throne” or “Emperor”, terms often used when describing “Emperor Xi” (or Emperor 11). Any references to “Game of Thrones” (Or “Game of Power” as the TV show is called in China) are blocked as well. In another recent case, the English letter "N" was banned briefly [3].

, which means “Throne” or “Emperor”, terms often used when describing “Emperor Xi” (or Emperor 11). Any references to “Game of Thrones” (Or “Game of Power” as the TV show is called in China) are blocked as well. In another recent case, the English letter "N" was banned briefly [3].

Chinese WeChat users also adopted a common spam filter bypass technique: They posted images instead of typing the text. Recently, WeChat started to use OCR to automatically filter these images. Starting last year, WeChat users off and on reported blocked images as a result. This is kind of impressive in that WeChat has just short of a billion active users who sent an average of 38 billion messages a day. The filters also only affect users inside China and are more likely going to affect group messages than personal messages, likely in an effort to optimize the use of computing power to affect messages with the most impact. Users outside China are able to use these words, which often leads to odd conversations in which users inside China see only part of the conversation in a group chat.

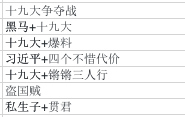

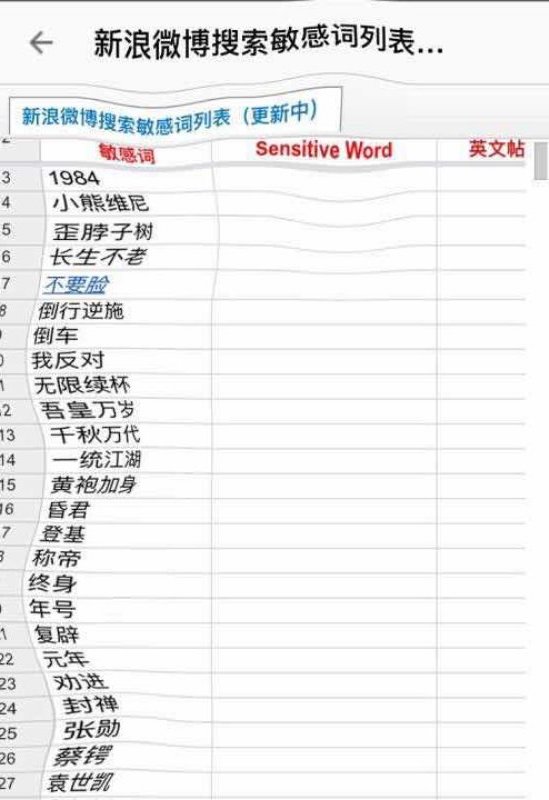

To experiment with the filter, WeChat users have used the following “test image” which includes many of the forbidden words (like “Winnie the Pooh”). Then they experimented with various distortion techniques to see if they can sneak words past the filter. This image, for example, was still recognized by the filter:

In a second attempt, they added lines to the heading of the image, which allowed it to sail past the censors

This is interesting in that the actual "bad words" in the list should still be easily recognized, but the only thing obfuscated is the header, which roughly translates to "Weibo Blocked Word List". While the header itself may certainly be included in the words to be blocked, the fact that the image sailed through the filters is likely due to the fact that not all images are scanned completely, but maybe only a part of the image is scanned, based on how frequent a particular image is used, and based on how busy the OCR system is at any time. Another possible reason is that instead of relying on OCR, the images are classified using a neural-net/machine-learning and removing the modified header will throw off the classification algorithm. Remember that this process happens as the image is being posted without any significant delay to the time it takes for the image to get posted.

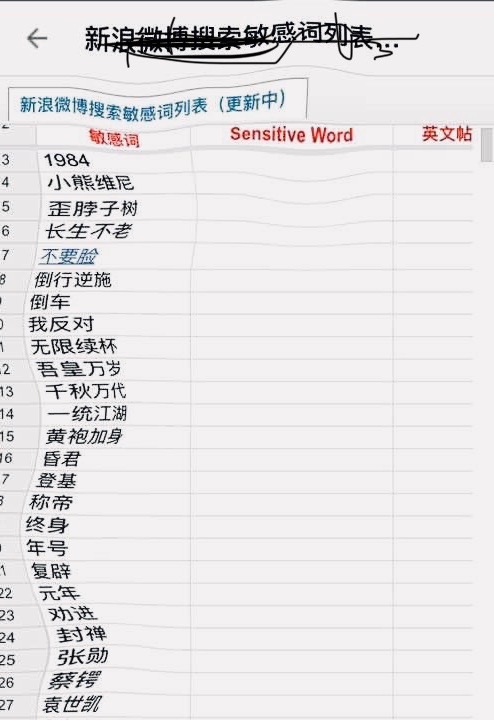

Just to show how quickly these keywords change, I created some test images, like the one below. It was not blocked even though it included numerous keywords from the Citizenlab study conducted last year. Turns out that the keywords apparently focused too much on the 19th Party Congress, which was a hot topic last year, but has finished now and activists, as well as censors, moved on to other topics.

But China has certainly come up with a way to not only filter keywords for billions of messages each day, but also apply these lists to images by performing large-scale OCR on vast amounts of images essentially in real time. The filter decision is usually made as the image is being posted, not later. While still struggling with recognizing the content in context, as many of these techniques do, Chinese activists find it more and more difficult to evade these filters effectively and to communicate with each other using state-controlled media like WeChat, which are the only real communication options given that many other services that do not comply with Chinese filtering laws are blocked. VPNs are still a thriving business in China even though there have been more and more attempts to restrict them as well. Like all large internet players, Tencent is heavily investing into AI [2]. Speech recognition and image processing, as well as video processing, are prominent areas this technology is applied to. Many WeChat messages are exchanged as voice recordings, another area real-time (or close to real-time) filtering can be applied to.

[1] Citizenlab.ca

[2] http://www.sohu.com/a/223222288_99985415

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/feb/28/china-bans-the-letter-n-internet-xi-jinping-extends-power

---

Johannes B. Ullrich, Ph.D. , Dean of Research, SANS Technology Institute

Twitter|

| Application Security: Securing Web Apps, APIs, and Microservices | Las Vegas | Sep 22nd - Sep 27th 2025 |

Comments

Anonymous

Mar 3rd 2018

7 years ago

Anonymous

Mar 7th 2018

7 years ago