Reviewing the spam filters: Malspam pushing Gozi-ISFB

Introduction

Researchers should review their spam filters to see what malware is getting caught. Security professionals should be aware of current practices used by criminals pushing malware, even if it has little chance of infecting anyone in their organizations. Reviewing the spam filters keeps provides a clearer picture of our cyber-threat landscape.

In today's trip through the spam filters, I found two emails with malicious attachments. These attachments are Word documents with malicious macros designed to infect a vulnerable Windows host with Gozi-ISFB.

Shown above: Never a good sign when the document asks you to enable macros.

Unfortunately, I cannot share the emails. Both emails appear to contain legitimate correspondence. They each include a chain of previous messages, and I could not easily redact the information like I normally do with other examples of malicious spam.

Therefore, this diary will focus on the attachments, follow-up malware, and network traffic.

What is Gozi-ISFB?

Gozi-ISFB is a variant of Ursnif, and today's traffic looked like an example shared by @DynamicAnalysis in a blog post on malwarebreakdown.com.

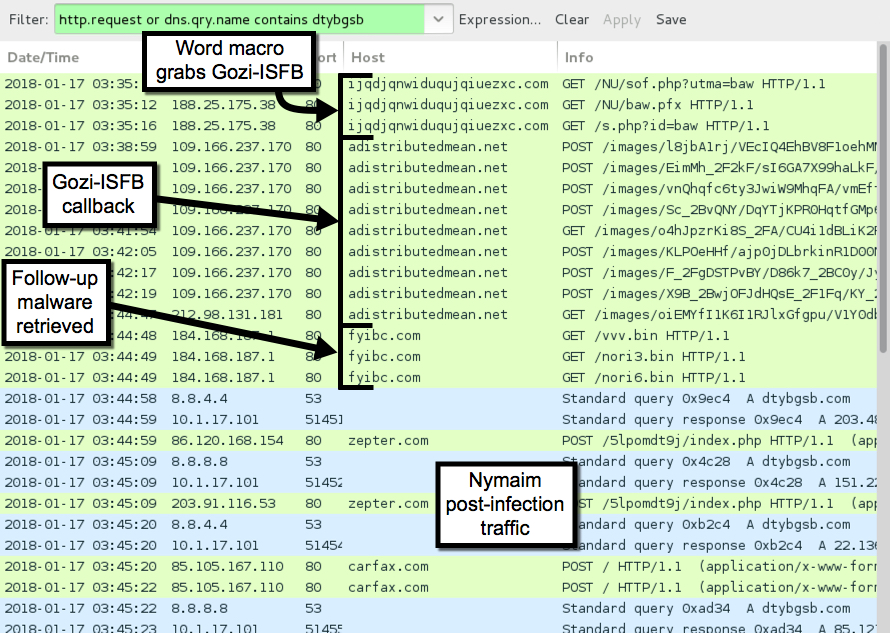

I generated two infections using each of the Word documents. In today's activity, about 8 to 10 minutes after the initial infection, the infected Windows host downloaded follow-up malware. Here's what I saw:

- 1st Word document --> Gozi-ISFB --> Nymaim Trojan

- 2nd Word document --> Gozi-ISFB --> unknown malware

The first infection followed-up with the Nymaim Trojan, and I've documented Nymaim traffic back in November and December of 2017.

Shown above: Traffic from the 1st infection filtered in Wireshark.

Since I've covered Nymaim before, I'm far more insterested in the second infection where I couldn't identify the follow-up malware.

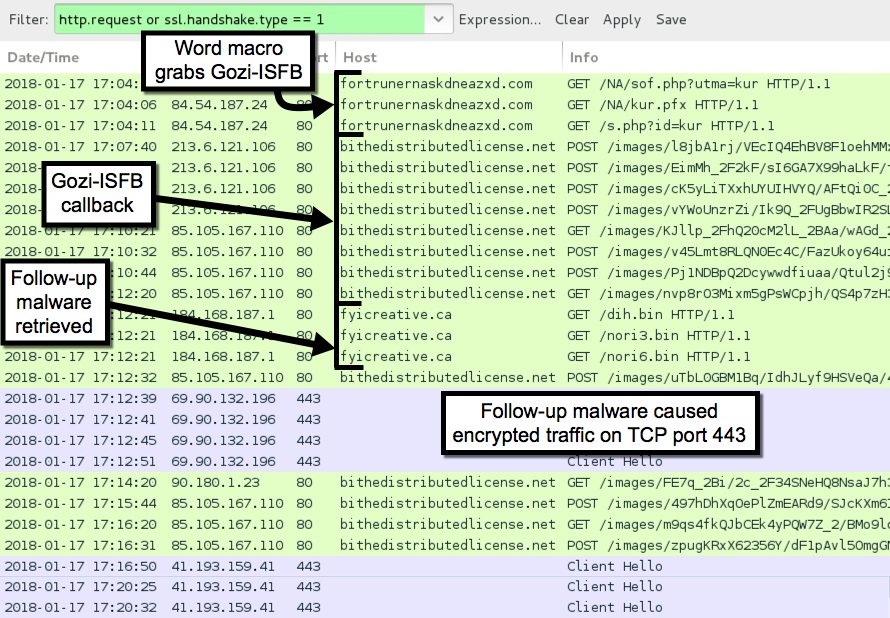

The second infection

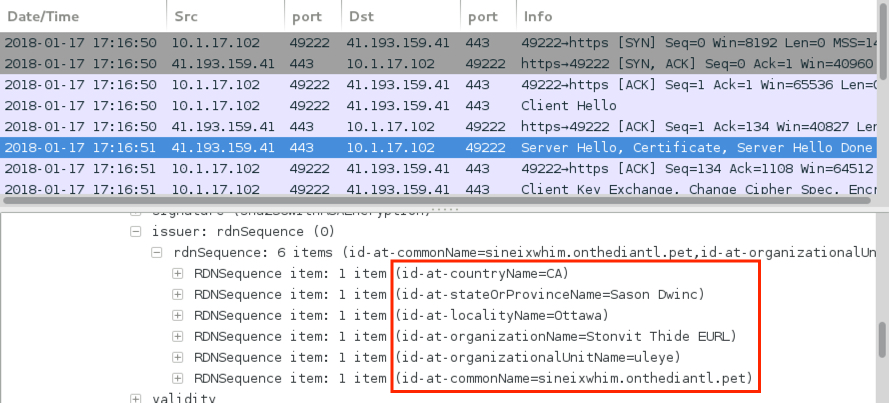

The second infection follows the same patterns as the first. However, this time the follow-up malware is different. I saw encrypted traffic with no associated DNS requests or domains. Two of the IP addresses had interesting certificate data as shown in the images below.

Shown above: Traffic from the 2nd infection filtered in Wireshark.

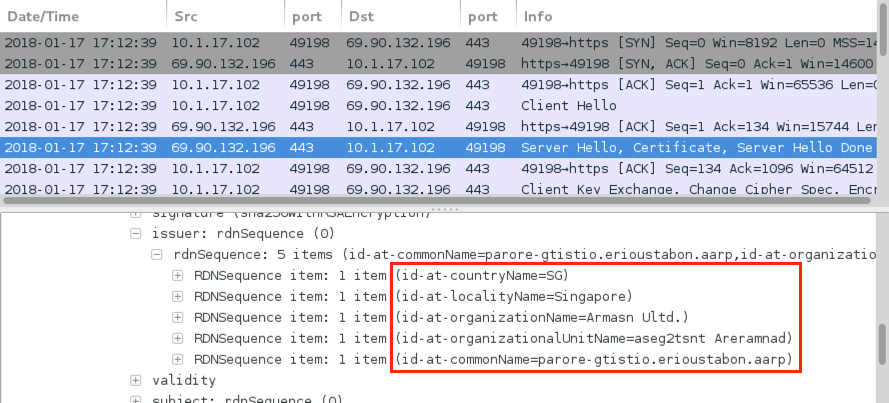

Shown above: One example of certificate data from the encrypted post-infection traffic.

Shown above: Another example of certificate data from the encrypted post-infection traffic.

Based on the network traffic and post-infection artifacts, I could not identify the follow-up malware. The follow-up malware is a malicious DLL named winmm.dll that's loaded by a legitimate Windows system file named presentationsettings.exe. Both were found in a newly-created directory under the infected user's AppData\Roaming folder. See the indicators section below for details.

Indicators

Artifacts from the 1st infection:

SHA256 hash: febb37762a92bedad337d0489ac482e356e2787533d65a757c3375fb147ff0a8

- File size: 55,248 bytes

- File name: Request.doc

- File description: Word document with malicious macro

SHA256 hash: 14284152d53c119ad04c986a2a115485ae480d8012603679bf28ec27e3869929

- File size: 1,101,824 bytes

- File location: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\52a8081a.exe

- File location: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Adsnsdmo\CRPPport.exe

- Associated Registry key: HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

- Value name: adprvmgr

- Value type: REG_SZ

- Value data: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Adsnsdmo\CRPPport.exe

- File description: Gozi-ISFB (an Ursnif variant)

SHA256 hash: d254e82bdbfd16aa9f0037e2c536c3b9dddd6ec559d26a5af005d3a1f8199d59

- File size: 580,864 bytes

- File location: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Local\molarity-24\molarity-12.exe

- Associated Registry key: HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

- Value name: molarity-96

- Value type: REG_SZ

- Value data: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Local\molarity-24\molarity-12.exe -s0

- File description: Probable Nymaim Trojan

SHA256 hash: f1c9544e8f1de92f60f13e29403fc459811b93a7a316d957cb30c1b4a61ba61d

- File size: 656,896 bytes

- File location: C:\ProgramData\wedge-46\wedge-6.exe

- Associated Registry key: HKCU\Software\Microsoft\WindowsNT\CurrentVersion\Winlogon

- Value name: shell

- Value type: REG_SZ

- Value data: C:\ProgramData\wedge-46\wedge-6.exe -46,explorer.exe

- File description: Probable Nymaim Trojan

SHA256 hash: 6e5faf4c3eb47a5218f173564fc1e5a8afc65a8126ff7f602e8dbfe98a2ba695

- File size: 651,776 bytes

- File location: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\aliasing-40\aliasing-2.exe

- File description: Probable Nymaim Trojan

Artifacts from the 2nd infection:

SHA256 hash: 044e86936bfc30cd0c07186b6e270650f896f6a42e9b8015abc184d161880090

- File size: 55,012 bytes

- File name: NBS_Request.doc

- File description: Word document with malicious macro

SHA256 hash: f8bdb65d54ccab04a506e84f14bdbeef15f6266a7bd6e4e7dfde69de424dd10a

- File size: 1,010,688 bytes

- File location: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\6d9be056.exe

- File location: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Bitsxapi\efsuvoas.exe

- Associated Registry key: HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

- Value name: dmusdBth

- Value type: REG_SZ

- Value data: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Bitsxapi\efsuvoas.exe

- File description: Gozi-ISFB (an Ursnif variant)

SHA256 hash: 208b94fd66a6ce266c3195f87029a41a0622fff47f2a5112552cb087adbb1258 (not malware)

- File size: 176,640 bytes

- File location: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\XPIALj1\PresentationSettings.exe

- Associated Registry key: HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

- Value name: Ehlho

- Value type: REG_SZ

- Value data: "C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\XPIALj1\PresentationSettings.exe"

- Start menu shortcut: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup\Ehlho

- File description: Legitimate system file that loads any DLL named winmm.dll in the same directory.

SHA256 hash: 018084df00799387be61c5f849af8fce093aab8f73420a2ece7b47d0f45fa07e

- File size: 176,640 bytes

- File location: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\XPIALj1\WINMM.dll

- File description: Malicious component called by PresentationSettings.exe

- File description: Malware DLL loaded by legitimate system file PresentationSettings.exe in the same directory

1st run infection traffic:

- 188.25.175.38 port 80 - ijqdjqnwiduqujqiuezxc.com - GET /NU/sof.php?utma=baw

- 188.25.175.38 port 80 - ijqdjqnwiduqujqiuezxc.com - GET /NU/baw.pfx

- 188.25.175.38 port 80 - ijqdjqnwiduqujqiuezxc.com - GET /s.php?id=baw

- 109.166.237.170 port 80 - adistributedmean.net - GET /images/[long string].gif

- 109.166.237.170 port 80 - adistributedmean.net - POST /images/[long string].bmp

- 212.98.131.181 port 80 - adistributedmean.net - GET /images/[long string].gif

- 212.98.131.181 port 80 - adistributedmean.net - POST /images/[long string].bmp

- 86.120.77.221 port 80 - adistributedmean.net - GET /images/[long string].gif

- 86.120.77.221 port 80 - adistributedmean.net - GET /images/[long string].jpeg

- 86.120.77.221 port 80 - adistributedmean.net - POST /images/[long string].bmp

- 80.80.165.93 port 80 - adistributedmean.net - GET /images/[long string].gif

- 80.80.165.93 port 80 - adistributedmean.net - POST /images/[long string].bmp

- 186.73.245.226 port 80 - adistributedmean.net - GET /images/[long string].gif

- 188.237.190.24 port 80 - adistributedmean.net - GET /images/[long string].gif

- 184.168.187.1 port 80 - fyibc.com - GET /vvv.bin

- 184.168.187.1 port 80 - fyibc.com - GET /nori3.bin

- 184.168.187.1 port 80 - fyibc.com - GET /nori6.bin

- DNS queries (using Google DNS) for dtybgsb.com

- 86.120.168.154 port 80 - zepter.com - POST /5lpomdt9j/index.php

- 203.91.116.53 port 80 - zepter.com - POST /5lpomdt9j/index.php

- 155.133.93.30 port 80 - zepter.com - POST /5lpomdt9j/index.php

- 85.105.167.110 port 80 - carfax.com - POST /

- 85.105.167.110 port 80 - zepter.com - POST /

- NOTE: carfax.com and zepter.com are legitimate domains and not compromised. They just resolve to bad IP addresses for dtybgsb.com due to the nature of this Nymaim infection.

2nd run infection traffic:

- 84.54.187.24 port 80 - fortrunernaskdneazxd.com - GET /NA/sof.php?utma=kur

- 84.54.187.24 port 80 - fortrunernaskdneazxd.com - GET /NA/kur.pfx

- 84.54.187.24 port 80 - fortrunernaskdneazxd.com - GET /s.php?id=kur

- 213.6.121.106 port 80 - bithedistributedlicense.net - POST /images/[long string].bmp

- 85.105.167.110 port 80 - bithedistributedlicense.net - POST /images/[long string].bmp

- 85.105.167.110 port 80 - bithedistributedlicense.net - GET /images/[long string].gif

- 90.180.1.23 port 80 - bithedistributedlicense.net - GET /images/[long string].gif

- 184.168.187.1 port 80 - fyicreative.ca - GET /dih.bin

- 184.168.187.1 port 80 - fyicreative.ca - GET /nori3.bin

- 184.168.187.1 port 80 - fyicreative.ca - GET /nori6.bin

- 41.193.159.41 port 443 - Encrypted traffic both with and without cerificate data

- 69.90.132.196 port 443 - Encrypted traffic both with cerificate data

- 69.75.114.66 port 443 - Encrypted traffic (no certificate data)

- 74.50.133.9 port 443 - Encrypted traffic (no certificate data)

- 41.193.159.41 port 444 - attempted TCP connections, but no response from the server

- 95.150.74.40 port 443 - attempted TCP connections, but no response from the server

- 179.108.87.11 port 443 - attempted TCP connections, but no response from the server

- 190.208.42.36 port 443 - attempted TCP connections, but no response from the server

Of note, during the first infection, I rebooted the infected Windows host 3 or 4 times, which might account for multiple copies of what I assume are Nymaim. If you review the pcaps, the reboots are indicated any place you see an HTTP request to www.msftncsi.com.

Malicious domains

Indicators are not a block list. If you feel the need to block web traffic based on this diary, I suggest the following domains:

- ijqdjqnwiduqujqiuezxc.com

- adistributedmean.net

- fyibc.com

- fortrunernaskdneazxd.com

- bithedistributedlicense.net

- fyicreative.ca

Final words

Pcaps and malware for today's diary can be found here.

Good spam filtering, proper Windows administration, and best security practices will ensure most people never see this malware. However, criminals are constantly tweaking their methods in an attempt to slip past our defenses. It pays to be aware of current malware indicators, so we're prepared if any ever make it into our network.

---

Brad Duncan

brad [at] malware-traffic-analysis.net

Comments

Anonymous

Jan 17th 2018

7 years ago

Anonymous

Jan 18th 2018

7 years ago

That's a very good question. If they are in fact legitimate emails, this implies a host used by the other email account (or perhaps the email account itself) communicating the with recipient is compromised. It's possible an infected host is using a local cache of an email client to send these messages. Unfortunately, without having access to the host at the other end of the conversation, I don't know how this is being done.

It's also possible these long email chains are completely fake, but what little I've seen indicates they are not. For example, signature blocks used by the recipient in previous correspondence from the email chain make me think these are legitimate conversations, and the host at the other end is somehow compromised. How this happened? I don't know.

Anonymous

Jan 18th 2018

7 years ago